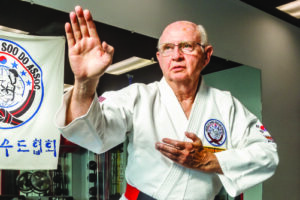

Transforming his body, mind: Bill Strong has spent 50 years studying Tang Soo Do

By Chelsea Retherford | Living 50 Plus

Bill Strong achieved his ninth-degree black belt in Tang Soo Do about four years ago, but even in reaching the pinnacle of his career, he said he still has much to learn and teach in the martial art, especially when it comes to developing mind-body coordination.

Strong, who has more than 50 years’ experience in Tang Soo Do, said he found a passion for the martial arts by chance as a college student at the University of Texas.

“It was offseason for us on the track team, and I just happened to see a little sign posted up that said, ‘Come watch people break bricks,’” Strong said. “I thought, whoa, I want to see that!”

After taking his first lessons, Strong found he cared less about seeing people breaking bricks and more about honing his skills that were transforming his mind as well as his body.

“It just felt good. It was physical and required some speed, but the skill level and the philosophical part of it — I was just getting into that part of my life too,” he said.

Strong continued studying and practicing martial arts in college until he moved to Florence in 1972, where he taught geography as a professor at the University of North Alabama for more than 40 years.

Here in the Shoals, Strong said he was introduced to Taekwondo, a Korean martial art similar to Tang Soo Do that involves combative styles of punching and kicking.

“Some people say that Tang Soo Do is a parent of Taekwondo,” Strong said. “Beginning in 1945, there’s a man that established an organization, and his name was Hwang Kee. He called it various things, but Moo Duk Kwan is how we shorten it, and that continued until it became the largest (martial art) in Korea. There were four others, and in the mid-1950s or ’60s, there was a general who kind of forced all those to come together into one, which was called Taekwondo.”

Though Strong practiced Taekwondo for about 10 years in Florence, he eventually met and began training under the late Grandmaster Jae Chul Shin, who is known as the founder of World Tang Soo Do Association (WTSDA).

“My grandmaster, Grandmaster Shin, started as a kid in that organization, Moo Duk Kwan,” Strong said. “He went to Korea University and got his master’s degree in political science and international studies.”

In 1958, Shin was drafted into the South Korean Air Force and stationed at Osan Air Base to teach Tang Soo Do to American and Korean servicemen, including Carlos Ray “Chuck” Norris.

“So, that all started in the late 1950s and ’60s, and that’s when Norris and the others came in,” Strong said. “These guys would graduate, get their degrees and come back and start studios.”

Strong said his path crossed with Shin’s while he was training in Huntsville under another instructor. When Strong had heard about Shin and found out that he was in the U.S. teaching, he said he gave the grandmaster a call.

Strong had already achieved his fourth-degree black belt through another organization, but after WTSDA was organized in 1982, Strong said he tested for his fifth degree in 1988 in Montgomery as Shin’s organization was just beginning to grow.

“That’s before the master’s clinic started,” Strong said. “We started the first testing during master’s clinics. It started at 10 at night and lasted to about 3 a.m. for three people. I was on the panel, and there were only three of us testing.”

Strong said it’s a common misconception among those not familiar in the martial arts that achieving a black belt is the end of the journey, but as he experienced, earning your first-degree black belt is the first steps towards mastery.

Similar to karate, Tang Soo Do’s belt system consists of 10 color belts and grades that denotes the student’s mastery or dan level.

“At each stage, there are a number of things you must learn,” Strong said, explaining that the belt system, beginning with white, typically requires the student to advance two stages of training before they advance to the next color.

Those training stages typically take about three months of training plus a requisite number of classes. When a student reaches the Cho Dan Bo, or dark blue, belt, the requirements to advance become more intensive, Strong said.

“Everyone is required to start learning the Korean terminology. It takes maybe three years to get there. Some people get up in two years.”

After achieving the blue belt rank, Strong said students are then required to master six to 12 months of additional training before they become eligible to take the initial black belt test, which consists of all the basics — kicking and punching — as well as traditional forms, called Hyungs in Korean.

“There are more than 30 of them, and I think one person calculated 2,100 moves you have to memorize to get to the highest levels,” Strong said. “It’s a lot to keep in mind, but you burn it in over time, especially to become a teacher. You get to become an assistant instructor after you become a black belt.”

Between each of the earliest degrees in the black belt stages, Strong said another two to three years of training are required before advancing to the next degree.

When a student achieves their fourth-degree black belt, there’s a minimum of five years to train, and even then, the student has to be invited to continue testing to enter the assistant and grandmaster levels.

“You have to have done all this stuff all the way up through third-degree, plus you’ve had to have made significant contributions to the association at large, to your school, to your community, and to yourself,” Strong said. “So, a lot of people start. Very few people are at the top.”

After all those years of training, extensive testing, and dedication to the craft, Strong said he still finds joy and purpose in not only practicing the art, but also in sharing it with others.

“I’ve probably skipped maybe one week of my life in the last 50-something years,” Strong said. “I can’t remember why I did that, but it wasn’t because I didn’t want to. It’s just something I do every day.”

Though he admits there are days he feels less motivated to stretch and flow through the motions — whether it’s a calming tai chi session or a more intense Tang Soo Do routine — he said he always finds a way to push through.

“I know self-defense is obviously a reason you do these things, but it’s not foremost in most people’s minds. It brings people together for a common purpose, and it strengthens your mind and body,” Strong said.

“What is it that Clint Eastwood says? ‘Don’t let the old man in.’ I’m happy to still be able to do it. I know this keeps me healthy.”